Sense and Sensuality

---Art-House Master Tsai Ming-liang discusses his new movie “The Wayward Cloud” and his philosophies in a moody, existential interview ---

By Andrew Huang

Contributing Writer

(This article originally appeared in Taiwan News on Friday, February 18, 2005)

For all the film buffs out there, Taiwan’s film world enfant terrible Tsai Ming-liang is back again with his new movie “The Wayward Cloud,” his bravest and most controversial work so far.

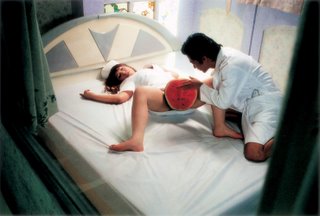

Tsai’s latest movie “Wayward Cloud” is a daring, envelope-pushing movie about the lives of pornography performers. Tsai’s long-term actors Lee Kang-sheng portrays a porn actor while Chen Shiang-chyi portrays a librarian girl who starts a relationship with Lee and ends up discovering that he is a porn actor. The movie contains colorful musical scenes and sexually explicit scenes. The movie is selected for the official competition section in the 2005 Berlin Film Festival, which will wrap up its week-long event and announce the winners on February 20.

An award magnet, Tsai has won awards with every single one of his movies. His debut movie “Rebel of the Neon God” won the Bronze Award at Tokyo Film Festival in 1993. His highly acclaimed second movie “Vive L’Amour” won the highly coveted Gold Lion Award and Fipresci Prize at Venice Film Festival in 1994. His third movie “The River” won the Silver Bear Award at Berlin Film Festival in 1997. His next movie “The Hole” won the Fipresci Prize at Cannes Film Festival in 1998. The 2001 movie “What Time Is It Over There” won the Grand Technical Prize at Cannes. The 2003 movie “Goodbye, Dragon Inn” won the Fipresci Prize at Cannes.

For this new movie which made its world premier in Berlin this past week, Tsai’s long-term collaborators also show up for this cutting-edge movie. Actress Lu Yi-ching portrays an older has-been porn actress who sings her swan song against the backdrop of an errie room filled with smoke and fire. Last year’s Golden Horse best actress winner Yang Kuei-mei portrays another porno actress who sings a song in another scene. A real Japanese porn actress also portrays a minor character.

As with all the Tsai movies, the revolutionary “The Wayward Cloud” contains minimal dialogues, almost invisible plot, continuous long shot and long scenes, lingering shots of human body parts that border on fetishism, dark-toned cinematography and, last, but not least, infinite possibilities for symbolic and metaphysical meanings.

Born in Malaysia in 1957, Tsai grew up in an idyllic small town named Kuching. The pace of life is leisurely and almost aimless in the small town. Tsai’s favorite pastime during his youth was to go to the various movie theaters to watch Hollywood movies. He wasn’t particularly interested in academic study.

At the urge of his father, Tsai moved to Taiwan when he was 20 years old to pursue college education. Tsai chose to major in theater study because movie study was not available at that time. He graduated from Taiwan Culture University with a degree in theater in 1981. During his college years, He started writing theater plays and also directed three short films. His short “Instant Minced Meat Noodle” in 1981, “A Door That’s Unopenable in the Dark” in 1982 and “The Closet in the Room” in 1983 all explore the themes of self-defense mechanism of modern urban denizens. This is also the recurrent theme in all of his later feature films.

After graduation, Tsai spent a decade working in television as a screenwriter. He started writing and directing his own single-episode TV drama since 1989. It’s during the shooting of a TV drama entitled “Child” (1991) when he accidentally discovered a youth named Lee Kang-sheng in a video game bazaar.

Lee later became the muse and Tsai’s alter-ego in all of his future movies. Tsai wrote and directed his debut feature film “Rebel of the Neon God” based on the non-professional actor Lee, who even used his real name as the character’s name in this movie.

I arrived at Tsai’s film company Home Green in Yongho area in Taipei County around 4: 30 p.m. on Sunday, February 6 for the planned one-hour exclusive interview. The company building is an old-fashion, almost derelict three-story old-structure housed inside a brick-and-cement square wall with a court yard in the center where a giant tree looms at the front of the building.

Tsai was in the kitchen cooking something when I entered. He told me to go up to the second floor. After I ascended the stairs, actor Lee Kang-sheng – who was surf the internet with her face lit by the glow of computer monitor in the first room – told me to go straight to the last room at the end of the corridor.

I went inside the room and sat down to pull out my cassette recorder and notes, waiting for Tsai. The room is a Japanese-style room with straw mats covering the ground and a long rectangular wood table in the center. Surrounding the room are massive amount of Tsai’s works including theater prints, video cassettes, promotional materials, reference books, scripts and books that pile up against the wall to the ceiling except the windows.

Ten minutes later, Tsai came into the room and sat across the table from me, pouring tea from a kettle and offer me my cups. Tsai looks exactly like the photos in the newspapers. He sports a very short hair that’s only an inch more than a shaved head. His facial structure is a curvy long shape with meaty cheeks and pouty lips. His eyes are so huge that they almost seem like they are bulging. His mouth is the shape of a two rivers twisted upwards at both ends so that he looks like he is smiling constantly even when he is not.

“The idea for ‘The Wayward Cloud’ started in 1999 when I went back to Malaysia for a trip. At that time, I wanted to write and director a movie about the south Asia foreign laborers who are often exploited and abused in Taiwan,” says Tsai. “However, that plan never panned out. Another four years passed. I thought, if I don’t do it, I will never get to make this movie. So I plunged in and made this movie ‘The Wayward Cloud’.”

Asked how the concept of a movie about exploited foreign laborers makes the astonishing leap to a movie about porn actors, Tsai explains, “It’s still the same idea but with different occupation. What I am interested in is in exploring the identity issue of these individuals who are caught and get stuck between two worlds. There are many foreign laborers who lost their work rights in Taiwan and they can’t go back to their own home countries. They are stuck in between two worlds. The same idea goes for porn actors. They live double lives as porn actors and normal people but end up stuck in between two worlds.”

“Originally, I wanted the Hong Kong actress Hsiao Fong Fong to portray an aunt who comes to Taipei to visit Lee and suddenly discovers that he is a porn actor,” Tsai says. “Hsiao is not available. Then I asked Hong Kong director Ann Hui to portray this part. She is very interested and willing to do it. Unfortunately, by the time when we started shooting this movie, Hui was busy with other projects. So I ended up having Li Shang-ling to play a librarian girl who dates this guy and suddenly discovers that he is a porn actor.”

Because of the subject matter of porn actors and Tsai’s unwavering faith in presenting the absolute truth as he knows on the screen, it’s reputed that the nudity and sensual quotient of “The Wayward Cloud” might even upstage Japanese master Nagisa Oshima’s “In the Realm of Senses” about a sexually sadomasochistic relationship which rocked the film world when it appeared in 1976.

“I really prefer not to talk about how much nudity there is in this movie because that is totally not the point. As with all my previous movies, ‘The Wayward Cloud’ is about the emotional life of these characters. Talking about the amount of nudity involved will simply mislead the audience,” Tsai asserts. “As a director, I also need to protect my actors. They give me their trust and strip naked to perform these characters for the sake of art. They deserve our utmost respect. This is not a porn movie. This is a movie about human emotions.”

I asked Tsai about the several important recurrent themes in movies: alienation in urban life, frustrated desires, unfulfilled love, deviant sexual behaviors and a deeply-rooted sympathy for people who live in the margin of the society.

“I moved to Taipei when I was 20 years old. That was a time when Taipei was still relatively innocent and simple. We used to have three TV channels only in that era. During that era of the rigid political climate, they even play patriotic songs on TV everyday,” says Tsai. “Then we went through the most drastic change that could happen to a city. Taipei has changed so much and becomes so complicated during the past two decades. Because I grew up in a very simple small village during my childhood, the change of Taipei leaves a huge impact on my mind and psyche. In my 20’s, there was a period of time when I could not spend time with anyone for more than 24 hours without freaking out.”

“The other thing is of course that -- I am a Chinese who is born and raised in Malaysia for the first 20 years of my life,” Tsai professes. “Even today, I feel I belong neither to Taiwan nor to Malaysia. In a sense, I can go anywhere I want and fit in, but I never feel that sense of belongings.”

“It’s also part of my natural personality trait too,” Tsai adds. “I am suspicious of the notion of a country, family or home.”

“The main point of my cinema is to pursue the truth, and there is nothing more truthful than when a person is being alone. When a person is alone, he doesn’t need to perform for anyone anymore. He simply does what he wants and be his real self,” Tsai explains. “I, for example, enjoy myself the best when I am peeing. That’s the moment when I am totally alone and do not need to pretend anything for anyone.”

“I also want to expel the notion is ‘solitude’ has to be a very depressing state. It’s a concept concocted by this society,” Tsai elaborates further. “’being alone’ does not necessarily means ‘being lonely;’ solitude can be a very happy state too.”

I nodded and applauded Tsai’s opinion on this. Then, a question suddenly pops up in my mind. “Tsai, I totally agree with you that solitude does not necessarily mean loneliness. It could be very liberating and comfortable, such as when I am reading and listening to music before going to sleep,” I said. “But according to this theory, half of the characters in your movies should enjoy their solitude too. How come all of your characters suffer and drown in loneliness?”

Tsai paused and thought about this for a while. He then agreed, “that’s a good question.”

For anyone who have sampled Tsai’s movies which are replete depression, suicide attempt, alienation, estrangement, fear and death, it’s naturally to be curious if Tsai Ming-liang the person spends his life in depression and is suicidal all the time too.

I asked Tsai if the alienation and depression in his movies mirrored his life. Tsai paused for a few minutes before answering, “I would say that my real personal life is a lot better than my movies. I have pretty good and steady friendship with my actors and crew, with other culturati and my own family --- but based on a finely-defined distance. I am still trying to find that fine point where I can have good relationship with people without colliding.”

Closely related to the theme of alienation is the sexual deviation in Tsai’s movies. In all of his works, there is a chain reaction of frustrated desires, unfulfilled love, and then sexual fantasies that lead to all antics such as masturbation, voyeurism, and casual, meaningless sex etc.

Tsai responded first by telling me a riotous joke about a presidential screening of his masterpiece “Vive L’Amour” in 1994. After the movie won the Venice Gold Lion Award, the then President Lee Teng-hui invited Tsai and his actors to go to the Presidential Building for a private screening. Tsai hesitated but accepted the invitation anyway. Tsai, his actors, President Lee and his staff awkwardly sat through this movie about a complicated triangle that involves masturbation, nudity and voyeurism. After the light came up, the audiences were speechless and trapped in a cloud of embarrassment. Ever a tactful politician, President Lee stood up to declare, “Well, masturbation! Everyone has done it. No big deal!”

After this laugh-out-loud tidbit, Tsai went on to explain his filmmaking philosophy. “I always feature characters who are sadly without love and lonely because that’s human beings at their most real,” Tsai says. “People have asked me why all the sex scenes in my movies are so sad and awkward. I tell them that because these two people are having sex without love. They don’t even know or care about each other enough, and of course their sex is awkward.”

“For me, solitude and sex are the moments when people are being their real self; there is nothing more real than solitude and sex as far as cinematic devices,” says Tsai. “My ultimate goal is to pursue the truth of human relation. Sometimes, even my actors ask me ‘director Tsai, do we really have to go to this extreme in our movie?’ My answer is yes. That’s my method of pursuing the truth.”

Asked about his sympathy for the socially marginalized people such as homosexual, porn actor, prostitute, handicapped and elderly etc., Tsai frankly responded, “I do not pretend that I have such a big heart and I want to push for social reform; my movies are about the lives of these characters rather than social reform.”

“It’s about my upbringing. I come from a small village where most people are working-class. My grandfather is a farmer. My father sells bowls of noodles on the street. I grew up helping to sell the noodles and washing the bowls,” Tsai reminisces. “After my grandfather passed away, my grandmother opened a Ma Jung casino in order to make a living. People from all walks of life came to the casino to play. I saw so many eccentric characters that might be considered ‘at the bottom of the social hierarchy.’ But I feel close to these people because I grew up with them. In my movies, I make no judgment about these characters. Whether they are gay or porno actor, they have the same feelings as other people do too. They are all human beings.”

Near the end of our interview, I took 20 minutes to confirm about certain information I read from a book entitled “Tsai Ming-liang” originally published in France in 2001. The book’s contributors include writers from Cahier du Cinema, the powerhouse magazine that launched the influential French New Wave movement. This book is apparently published with the collaboration and approval of Tsai and is undisputedly the most authoritative book about Tsai in both Asia and the western world so far. Tsai’s mood, however, shifted from his jovial chatter earlier to an impatient stance.

I ended my interview by asking an essential and entertaining question, “Have you ever considered making the movie that every Chinese director in the world wants to do now --- a kungfu movie?”

Suddenly, Tsai exploded into a tempest of tantrums, screaming at while jumping up and down on the straw mats. Tsai accused me for asking “stupid questions.” He told me, “I overestimated you! I thought you are from the English press and your questions will be more intelligent! But you are like some of those Chinese press! All they care about is nudity, dirt and scandal!”

Although a darling of prestigious international film festivals, Tsai has frequently come under fire with the Chinese press. He was harshly criticized for the depiction of father-son homosexual bathhouse incest scene for the movie “The River” by gay rights organizations and advocates. He is also attacked by feminism groups for his more focused careful attention on the male characters in contrast to the often trivial, abused female characters.

“Why does everyone think it’s the most important thing to make a kungfu movie or go to Hollywood?!” Tsai scolded. “Is that all there is about in this world? Kungfu movies and Hollywood?!”

I denied the charge that I ever asked Tsai if he wanted to go to Hollywood. Then I spent the next 50 minutes explaining the logic behind my every question while Tsai raved about the Chinese media which have unfairly criticized and labeled him.

Tsai calmed down after 50 minutes. Then I spent another 10 minutes to explain the logic and the importance of the “kungfu movie question. Three internationally acclaimed Chinese directors – Ang Lee, Zhang Yimou, and Chen Kaige – have made foray into the kungfu movie genre. Two others, namely Wong Kar Wai and Hou Hsiao-hsien, have announced their plans to make a kungfu movie. As Ang Lee puts it, “every Chinese director wants to direct a kungfu movie.” Does Tsai -- who has paid tribute to kungfu master King Hu’s classic “Dragon Inn” with his “Goodbye, Dragon Inn” – has the desire to attempt a kungfu movie too? Finally, Tsai gave me his answer: “of course.”

Tsai escorted me and the photographer who accompanied me on this assignment downstairs and to the door. Tsai invited me to go to the screening of “The Wayward Cloud” when it opens commercially this June and invited me for another interview with him.

I left Tsai’s company in a state of shock and went home to rest. Rick Yi, the photographer, got into a car accident that night after leaving Tsai’s company. Yi was hospitalized and released the next afternoon. When he turned up his camera the next day, Yi was shocked to find the images of Tsai inside. It took a few days for the memories of this Tsai interview to come back to Yi. However, Yi still does not remember how he got into the car accident that night.

The experience of this Tsai interview could be best described as “life imitating art.” I, Tsai and Yi sat in that conference room that was spacious at first and then grew claustrophobic with fear, anxiety, isolation, anger permeating the whole space. This interview and its subsequent consequences is a real life version of a Tsai Ming-liang movie with a 2-hour continuous long take interview, fear and alienation, a car crash and loss of memories.

This writer wants to ask the same question Tsai’s actors have posed, “do we really need to go to the most extreme?” Does the truth of human experience only exists in the most extreme, dangerous and dark corners? Is there more to the human experience other than loneliness, fear, alienation and incest? Aren’t the happier sides of solitude and sex as truthful to the human experience as the dark sides? As talented a filmmaker as he is, Tsai apparently still has a lot of thinking to do in his cinematic journey of pursuing the human truth.

Comments